Hello ACDA. It’s been a while since I have posted a blog here. I decided to cross post this one over from the Choralosophy Community Substack because it may be of particular interest to our membership. Namely, is it ok to advocate for “Choral Music” programs in school? Is it ok to argue for robust course offerings of choirs of multiple levels? How about a vocal music program of ONLY choir based on the idea that they scale better, and that we can more kids in there getting a music education in comparison to other types of music classes? Not all of us agree about this, and it’s an important discussion.

Please read, consider, and let me know what you think!

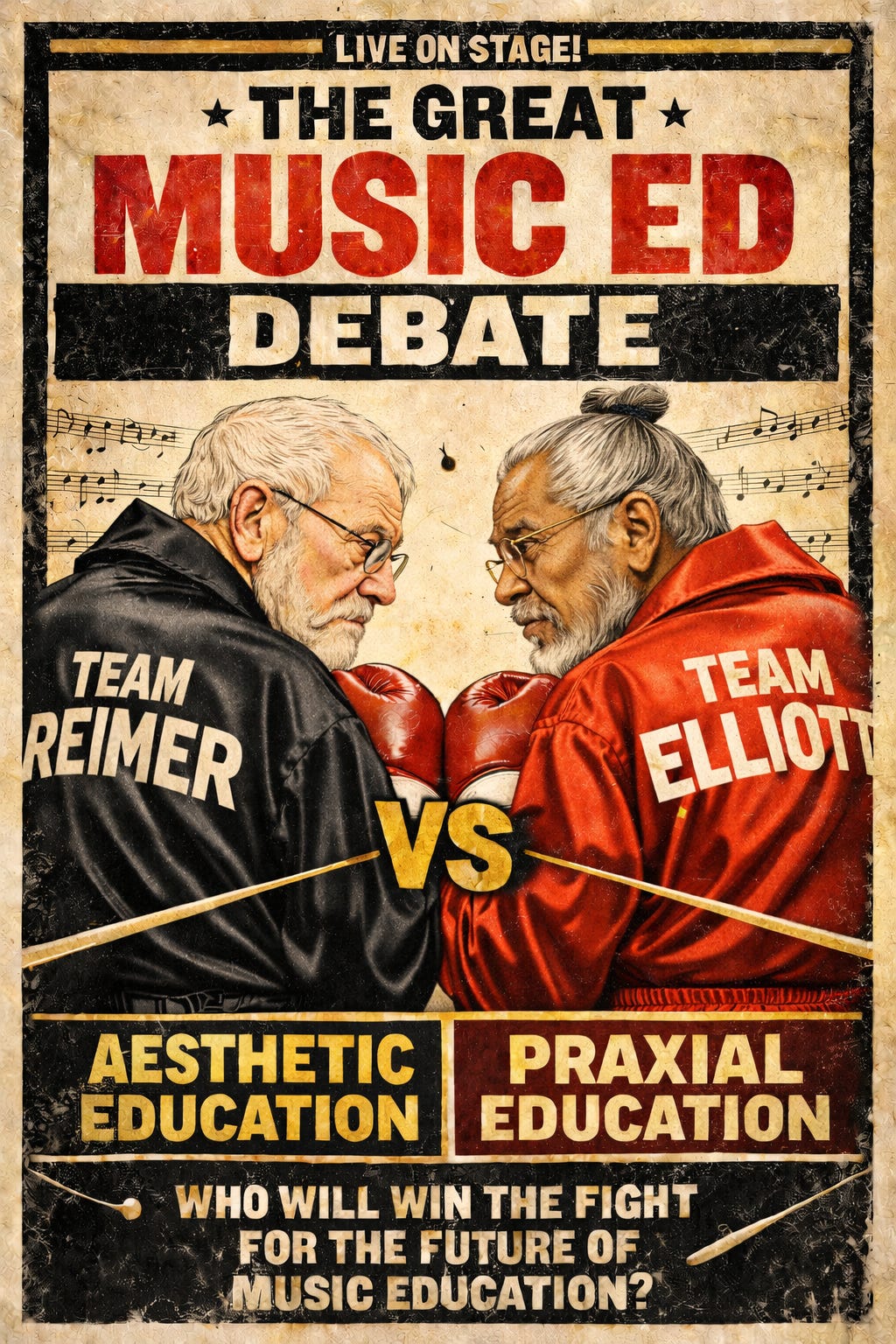

From Reimer vs. Elliott to Today’s Debates Over Ensembles

Every once in a while, the field of music education stumbles into a debate that isn’t really about repertoire, classroom strategy, or innovation — but about the meaning of the entire enterprise. We’re in one of those moments right now. And, I will start with a disclaimer:

Before going any further, I need to clarify what I mean when I use the word inclusive in this post — because it’s a term that now carries a lot of ideological weight, and I want to be precise rather than rhetorical.

When I talk about inclusion in school music, I am not primarily referring to symbolic representation, stylistic trends, genres, or whether students immediately recognize the repertoire as “their music.”

I am talking about structural inclusion.

By inclusive, I mean music classes that:

- have a low barrier of entry in terms of prior musical knowledge or skill

- do not require private lessons, personal instruments, or expensive equipment to participate

- are affordable to operate for public schools or other organizations over time

- Can it scale? Or, serve large numbers of students during the school day

- allow access to many genres, cultures, and historical traditions without requiring specialized gear or prior training

- and give students enough time and continuity to actually get GOOD at basic musical skills that transfer to other music. (Pitch, beat, rhythm, harmony, literacy etc.)

In other words, I’m defining inclusion not by intent or messaging, but by who can realistically walk through the door and stay.

This definition is deliberately practical. Public schools operate with finite time, finite money, and finite staffing. Any serious discussion of music education has to account for those constraints — not pretend they don’t exist.

So when I argue that some models labeled “more inclusive” are, in practice, less inclusive, I’m not making a moral claim about teachers’ intentions. I’m also not disparaging those other types of classes. I say, the more the merrier in terms of modes of music instruction. I think we should shamelessly advocate for the types of music classes we want to see. In my case, I am a shameless “choir program” advocate. Despite receiving criticisms that choir is “inherently exclusionary,” is part of “white supremacy culture” and that it is “not ok” for a school to intentionally create and offer a “choir program.” (Yes, actual feedback I have received.)

I’m making a structural claim.

Not that choral music programs are PERFECTLY inclusive. Just that they get us the closest to that dream.

That’s the lens I’m using for everything that follows in this article.

The divide I often see in Music Ed discourse usually gets framed like this:

- Ensemble Model Teachers — choir, band, orchestra — say music education thrives when students rehearse, perform, and develop deep musical skills together.

- General Music / “Student-Centered” Advocates argue that ensembles are exclusionary, outdated, and disconnected from the music kids actually care about — and that programs like Modern Band, songwriting, and production better reflect today’s world.

It’s also important to define what people mean by student-centered. This term has a fairly specific meaning in education research, but it’s often used more casually in everyday conversation. Colloquially, many people interpret student-centered to mean something like “holding students’ best interests at the center of our practice.” That’s a definition I agree with and one I’m comfortable using.

But when “student-centered education” shows up in district initiatives and reform movements, it usually means something more specific: instructional models that emphasize student agency, choice, relevance, and flexible pathways—often through inquiry-based or project-based learning. That distinction matters, because debates about music education can end up talking past each other unless we’re clear about which definition we mean. And many in Music Education, especially in schools of music ed teacher training see this version of “student centered” as directly in conflict with the “ensemble model” of music education. This is where I disagree in the strongest possible way.

But this isn’t a new divide. It’s just the latest round, newly packaged, in a philosophical argument that burst into the open in the 1990s, when Bennett Reimer and David Elliott clashed over a deceptively simple question:

What is music education in a school context actually for?

Because we can’t duck the reality: schools exist in a world of finite time and finite money. Whatever we emphasize, we emphasize at the expense of something else.

So the question isn’t just what sounds good in theory. And it isn’t a question of how ALL classrooms and programs must be set up.

It’s: Where do students — and the public — get the biggest return on investment in time, access, and educational value?

The First Divide: Reimer vs. Elliott

Bennett Reimer anchored his approach in aesthetic education. Music mattered because it deepened perception, imagination, and emotional insight. Diversity of styles and reflective listening weren’t side-notes — they were central.

David Elliott, in contrast, pushed a praxial view: music is something humans do. Meaning comes from participation — performance, rehearsal, improvisation, creation — inside real musical communities. And by “real” we mean functional.

Both men were thoughtful. Both arguments had merit.

But their disagreement planted a seed that’s still bearing fruit today.

- Reimer’s lineage → broad exposure, reflection, aesthetic and cultural awareness

- Elliott’s lineage → doing music deeply, skillfully, socially, repeatedly

Reimer’s aesthetic philosophy framed music education around the cultivation of deep musical experience and understanding, valuing both appreciation and participation but justifying it primarily through aesthetic meaning. Thoendel Philosophy

Elliott’s praxial philosophy argues that music education should begin with music as activity — doing, making, practicing — and that this praxis is the core source of musical understanding and value. (Victoria Boler)

Both perspectives acknowledge doing and listening, but they differ in where they place the primary purpose of music education.

And the more you look at the systems we’ve built since then, the more obvious it becomes:

America doubled-down on Elliott’s praxial model — and built the largest in-school ensemble ecosystem in the world.

Choirs. Bands. Orchestras. Every day. During the school schedule. Open to “normal” kids. No prior experience required.

This is rare. Other countries look at our system with a mixture of envy and disbelief.

And — uncomfortable as it might be to say — that system is also what funds full-time music education careers. One of the reasons for this is the scalability of the ensemble. Put in crass economic terms: school districts can occupy the schedules of more students with less teacher salary dollars when they offer robust music ensembles.

The New Divide: “Doing Music Together” vs “Relevance + Student Choice”

Fast-forward to today, and the philosophical language has shifted. We now hear:

- decolonizing music education

- student-centered learning

- relevance to modern youth

- challenging Eurocentric traditions

And I get it. Those concerns and criticisms they generate didn’t come out of thin air. There have been real problems worth addressing.

But the practical effect has often been this:

Ensembles are painted by critics as exclusionary relics, while small, modern, boutique programs are framed as the future.

On the the other hand, programs like Modern Band for example, get described as “more inclusive” and “culturally relevant” because students are performing music from their own cultural world, and do so while shirking the traditional “conducted ensemble model” which also upsets hierarchies. An idea that is very in vogue.

Meanwhile, ensemble teachers — particularly in choir — are quietly looking around thinking:

“Hang on… our classes are actually where the most kids participate — including total beginners — and at the lowest cost. We are the MODEL of inclusion.”

It’s a fair point. And it’s also fair to operate and advocate for Modern Band. Do we all need to structure our programs the same way? I say no.

The Scale Problem

Let’s step away from ideology and look at capacity.

Modern Band / production / songwriting courses typically:

- cap around 12–18 students

- require expensive, fragile technology and equipment

- most often admit students who already play a modern band instrument

- depend on schedule space schools rarely have in abundance

They can be thrilling. They can be meaningful. They can attract students that band, choir and orchestra do not. But they do not scale.

Choir, band, and orchestra routinely:

- enroll 40–80+ students per section

- welcome total beginners

- teach from scratch

- cost dramatically less per student

- give public-school kids access to real musicianship without private lessons

If equity means who can realistically participate, at scale, inside the school day — ensembles still win by miles.

Especially choir.

“But Modern Kids Need Modern Music!”

This is the loudest refrain. And sure — contemporary repertoire matters.

But here’s the part almost nobody says out loud:

Students don’t stick with music because they already liked the songs.

They stick because they become competent — and belong to something. And they don’t JOIN because of the repertoire either. They join for social reasons.

Mastery → confidence → identity → persistence.

That chain works regardless of genre.

If you weaken any link in that chain, participation drops.

And when participation drops?

Programs shrink.

Budgets shrink.

Jobs disappear.

That isn’t a “defense of the status quo.”

It’s economics.

The Financial Reality We Prefer to Ignore

A 60-student choir costs almost nothing to operate.

A 15-student music production course can require tens of thousands of dollars in gear — plus maintenance — plus space — plus IT support. Plus, 4 sections of the course just to get to the 60 the choir has. Which means 4 times the teacher salary dollars.

And the uncomfortable truth:

When boutique programs replace scalable ensemble offerings, far fewer students receive music instruction — especially low-income students.

That isn’t equity.

That’s well-intentioned exclusivity.

Back to the Core Philosophical Question

Which brings us back to Reimer and Elliott — and the unavoidable question they sharpened for us:

In schools — with limited time and money — what is music education actually for?

If your answer prioritizes:

- cultural sampling

- reflection

- exposure

- identity discourse

then the modern general-music movement looks attractive.

But it also risks producing breadth without depth.

Students “touch” and “experience” everything, but they master nothing.

They don’t feel like musicians, so they sample and then drift away.

UNLESS the program only admits the kids that already feel like musicians.

If your answer prioritizes:

- participation

- rehearsal

- technique

- ensemble identity

- performance

you land closer to Elliott:

music as a lived, practiced action.

And the results are:

- mass participation

- strong school-day music culture

- community visibility

- professional sustainability

- lifelong musicianship for thousands

That’s not just “in theory.” The side by side experiment is happening every day. Compare the US to the UK for example.

That’s what the American ensemble model has actually delivered in comparison to the rest of the world. Now, when compared to Utopia (100% of people participating in whatever music they enjoy at school from K-12 with no barriers to entry, or concern for finances) then, of course, our ensemble model falls short. But, everything falls short when compared to Utopia.

The Part That Should Scare Us

Right now, much of the field is drifting — sometimes quietly, sometimes militantly — away from the ensemble model in the name of social virtue and relevance.

But if we weaken the very system that gives millions of kids access to real music-making, we may not get a second chance.

Because once participation collapses, it doesn’t rebuild easily.

We’ll end up like many other countries, where music education becomes a small, elite after-school activity for families who can afford it.

Tell me:

How is that more inclusive?

My Answer to the Reimer-Elliott Question

Here’s where I land.

In the public-school context, the primary mission of music education should be to provide large-scale, praxial opportunities for students to become capable musicians through shared ensemble music-making.

But… I do not think the ensembles have to be “traditional” or “Eurocentric.” I think many different communities will find utility in a variety of types of ensemble. I don’t care if it’s a “Kazoo choir.” As long as we are considering the barriers of entry, rigor, literacy, scalability etc. I think the sky is the limit for what “ensemble” can mean in schools.

Then — from that strong foundation — we widen the circle:

- integrate diverse traditions

- respect student identity

- incorporate modern styles

- expand access thoughtfully

But we do not burn down the house to remodel the kitchen.

Because like it or not:

Ensembles scale.

Ensembles include.

Ensembles build competence.

Ensembles sustain the profession.

And — most importantly —

ensembles let ordinary kids become musicians.

That’s not exclusionary.

That’s the most democratic vision of music education we’ve ever built.

And it would be tragic — truly tragic — to dismantle it because we forgot to ask the oldest question in the book:

What is music education for?

I would also love to hear what you want to hear about in 2026! You can also apply to appear on the show to discuss your passion points at Choralosophy.com

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.