By Ayana Haviv

Tomorrow I begin rehearsals on Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, as I have done with countless Passions over the years, and as always I am steeling myself for the isolation and alienation I feel as a Jew singing this intrinsically and unquestionably anti-Semitic text of an equally unquestionable masterpiece.

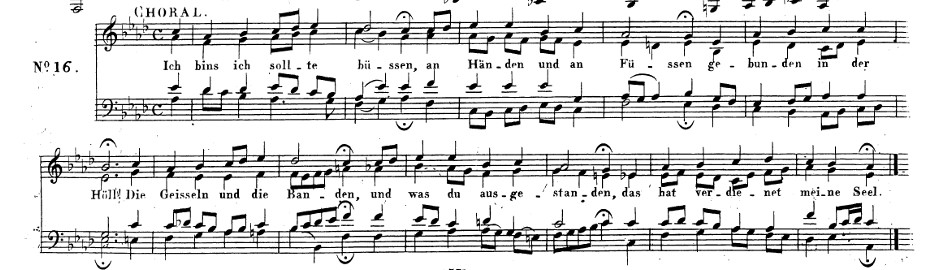

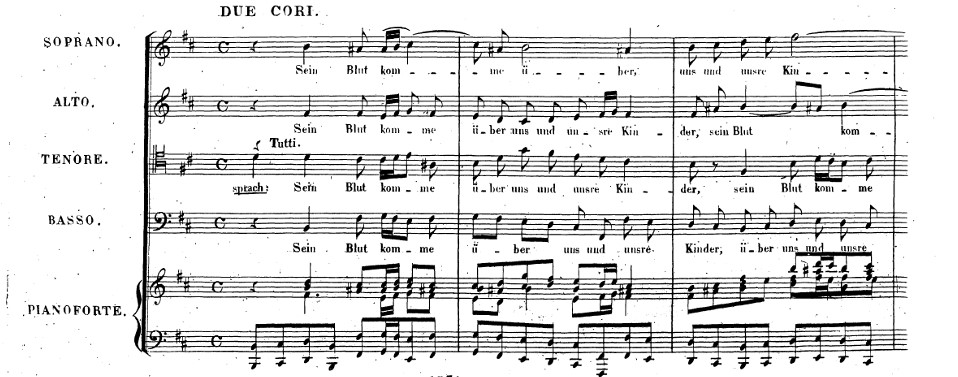

In the great classic Passions, there are always several anti-Semitic scenes, most obvious of which is the one where we, the chorus of Jews, sing of our blood lust and of how much we want Jesus killed. The sound of a noisy obstinate lynch mob, sometimes with caricatured witchy voices, are added by the composers and their interpreters, but the text is from the Gospels. Those were written in Greek, not Hebrew, for a reason: to try to persuade the Romans and other pagans, not fellow Jews, of the tenets of Christianity. It would never do to blame the Romans for Jesus’ death if they were trying to convert them; instead, the authors of the Gospels made the Jews the central villains of their story. It is the Gospels, not only Bach, who quote the murderous Jewish mob as cursing themselves: “his blood be upon us and on our children.” (See figure below.)

Note to figure: The contradiction at the crux, the most sublime & the ugliest: the congregation joins with the disciples in a gorgeous, heartfelt chorale taking collective responsibility for Christ’s death with “I am the one, I should pay for this;” a few pages later, the mob of Jews willfully curse themselves and their descendants with “His blood be upon us and on our children.” Johann Sebastian Bach, Matthäuspassion, BWV 244, images from Complete Score #569101, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, IMSLP

What many today do not know is what used to happen when these Passions were sung during Holy Week in Europe in the Middle Ages, Renaissance, and well beyond – they were sung in church, accompanied by fiery sermons also blaming the Jews for the murder of Jesus, and then the riled-up congregation would go out and murder a bunch of Jews. This was not at all rare – these Holy Week massacres happened so often that surviving records are often cursory and formulaic. Good Friday was especially notorious, and often priests/pastors themselves would lead their congregations in stoning Jewish houses, burning ghettos, and far worse. Christians of the era received the message on Good Friday that the Jews in their midst were their enemies, having killed their savior; only by converting to Christianity could they escape divine punishment. This did not go away with the Protestant Reformation – Martin Luther’s 1543 treatise “On the Jews and Their Lies” calls for the synagogues and Jewish homes to be burnt down by faithful Christians, even lamenting “We are even at fault for not striking them dead.” Catholics were just as bad. Even in Bach’s time, there were also those who argued for a more universal interpretation and less blaming of the Jews – yet the liturgy mainly stayed this way until after World War II, when some churches realized their own teachings’ contribution to the Nazi genocide. That was a welcome development, though not universal, and obviously not entirely successful in eradicating the myth that the Jews killed Jesus or its use as an excuse for violence.

To return to my experience singing these pieces – it is incredibly isolating knowing this bloody history in which many of my ancestors were murdered, and also knowing that my colleagues as well as the audience remain mainly blissfully ignorant of this context. In all my years of reading program notes, I have never once read anything of how Bach’s Passions affected the Jews who were his neighbors. I have seen passing mention of the anti-Semitism in the “kill Him” often with some boilerplate explanation/excuse – Bach was a product of his time, and so on. And indeed he was. But shouldn’t audiences and performers know a bit more about exactly how murderous these times actually were toward the Jews who are a central part of the story? Shouldn’t they know some of the consequences of the text and music that they are appreciating as art in the safe, elegant concert hall – let alone as part of a religious service?

Instead, both audiences and my colleagues shrug the words away. As singers as well as appreciators of Western art music, we are painfully accustomed to Christian liturgy and to compartmentalizing, after all, especially if we as individuals are not believers in the text.

Of course, I am not arguing that we stop performing these masterpieces. The Bach Passions are hardly the only canonical works whose artistic merits earn them a place in contemporary programs despite these issues. I also am extremely familiar with problematic source texts – the Hebrew Bible is certainly one, not just the Gospels – which require creative interpretation to clear away the centuries of bigotry and close-mindedness in order to get to the valuable nuggets underneath. This is a worthy endeavor in all religious traditions.

But some context can go a long way, and also make the Jews around you feel less alone. It’s not only that people don’t know; what hurts is that they don’t care.

Notes

- Daniel Joslyn-Siemiatkoski, “Why Good Friday Was Dangerous for Jews in the Middle Ages and How That Changed,”The Conversation (April 15, 2019), accessed March 3, 2022, https://theconversation.com/why-good-friday-was-dangerous-for-jews-in-the-middle-ages-and-how-that-changed-114896

- For more on the tension in Bach’s world on the theological question of the Jews see Alex Ross, “Holy Dread,” New Yorker, January 2, 2017.

Author’s note: A version of this article was originally published on social media on February 18, where the author’s chorusmaster at LA Opera, Grant Gershon, saw it, sent it to the author’s fellow choristers, and incorporated it into music preparatory rehearsals. Maestro James Conlon incorporated portions into the pre-performance lecture and program notes. The author is extremely gratified that in this case, her employers certainly did care.

Ayana Haviv is a chorister at LA Opera and Los Angeles Master Chorale, and sings on numerous film and television scores.

debisimonsgmail-com says

Hello! Thanks for this perceptive and enlightening article. I belong to a community choir and I’ve always kind of wondered what it’s like to sing lyrics in which you absolutely don’t believe. We do lots of traditional Christmas music, for example, and have a number of Jewish members. One of our tenors is a professional cantor at his synagogue and sang the “Pie Jesu” from some Mass or other once. I’m ashamed to say that I honestly didn’t know about these Good Friday massacres, although I certainly knew about other persecutions that have taken place under the guise of spirituality. We Christians (and yes, I am an Evangelical Christian) are sometimes shockingly ignorant and insensitive. So I appreciate the effort you’ve made here to open our eyes!

Thomas Lloyd says

Thank you for this valuable reminder and expansion on the long history of violence against Jews associated directly with the accounts of the Passion in the Christian gospel accounts. As you point out, there is inflammatory language in the original narratives themselves that provided the basis for this history of violence.

But I’m not sure the cause of promoting greater awareness of this important historical context is helped by suggesting that the gospels were written in Greek because the writers were only concerned about persuading Romans and pagans, and therefore felt free to write so derisively of the Jews. Most scholars agree that the gospel of Matthew was probably written in the context of a particular Jewish community, reflecting a then localized dispute over whether Jesus was the Messiah. Much later it became one of the scriptures that was considered more broadly authoritative for inclusion in the Christian bible, aside from its original context.

Greek was the most common spoken and written language of the day throughout the empire; the Hebrew bible was translated into Greek three centuries before Christ, and leading Jewish philosophers of this period such as Philo of Alexandria and Flavius Josephus also wrote in Greek.

Of course, there is still no doubt at all that these scriptures have been used by Christians to stoke the hatred and violence of anti-Semitism in the centuries that followed and into our present day, or that this history should be a part of how any musical or oral rendering of the Passion narratives are presented. Thank you again for bringing this issue to the fore.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Septuagint

Elizabeth Alexander says

There are simply not enough words for me to express how moved and impressed I am by your article. I wish everyone who makes music everywhere could read it with open eyes and hearts. If we all took your council to heart it would change so much about how we relate to works of the past, and to all lives in our own time. You communicate with equal parts pain, wisdom, and compassion, an exceedingly rare thing, and more precious than gold. Thank you.

Cherie Ploof says

I am so sorry. I never knew. When our college choir performed this we sang it in German and I never bothered to dig into the translations. There’s so much in history that I and others obviously don’t know or have been oblivious to. Thank you for bringing this awareness.

ayanahaviv says

Thanks for reading and learning the history!