Transcription of the address presented March 19, 2021

Greetings, dear Friends and Colleagues. It’s a pleasure and an honor for me to be with you today. The only thing I wish is that we could be here together and singing. That would be the best. But since that’s denied us for the moment, let me talk a little bit about my own experiences, what I’ve learned over these years of working in our profession, and end up with a wish for all of us for the future.

The basic truth is that music is sound. It is only sound. It’s as if all of our other senses were closed off to us and we were like fish in a bowl who know very well the world of water but have no idea of the world outside the bowl. Can we live in that world of sound so completely that we respond to every current, every tiny motion of the sound waves around us? Those sound waves, of course, live in time and space. Time is rhythm and space is all the acoustical elements, the speech, the pitch elements of music. We live in this dual world responding to its various pressures. It’s such a complex world, when you start playing with time and space and music; you are playing with the basic elements of creation. They end up in a song or they end up in a world in which we communicate with each other through this world of sound waves.

The tiny baby knows already how to sing, how to breathe. That first cry is far closer to song than it is to speech. And speech is language communication, learning to put into words our feelings, our wishes. And when that language develops it is capable of both profound insights in poetry and the most elementary laundry lists or shopping lists.

Song, I think, is based on language in that it is based on the intricacies of spoken language itself. It is impossible to notate the intricacies of language, so when we see the words to a song it behooves us to be careful how we speak them, that we speak them so that they transmit what they mean, not just recite them. If we organize the rhythms of the spoken language into a meter, that’s a step towards music. And if we organize the pitches, the little ups and downs of our daily speech, transmute them, expand them into melodic curves, then it’s the exultation of language somehow that comes into song. And what the song ends up communicating is far more than what it looks like on the page. It is not what we are singing about, it is not only that. It is not only rhythm or pitch or form, it is an inward communication of states within ourselves as human beings.

I can recognize a love song from another culture. I can recognize a child’s song. In fact, children’s songs around the world are remarkably similar in different languages. Certainly a song that grieves, a song that remembers, they have characteristics around the world that are very different according to the culture that they come from – and each one of us comes from a culture – and we should be able to honor the great experiences that have arisen within that culture.

We should also be able to say that each one of us can honor the culture of the others among us, because we limit ourselves terribly, we impose a limit on the world of sound, if we say we can’t understand your culture. We’re just not listening enough. We haven’t entered into the world of sound enough to be in that culture.

My favorite example of this is the Black spiritual. It arose in this country as a result, or out of the mouths of people who were subjected to incredible difficulty. But in a large sense, in the big sound sense, [it’s the combination.] The language of spirituals is the combination of the Black heritage from Africa – of an ear culture [and] a highly artistic culture, where there was not this separation of song from dance from language from poetry – the combination of that Black influence from Africa and the white influence from Europe out of which most of our . . . my, I should say, background comes from studying great classical music. When those two streams met together they were somehow refined in the spiritual to give us a language of music in which our innermost states could be united. I don’t know any other music like it. A Black spiritual can stand right after the Bach B minor Mass as an equal in communication. Somehow the folk music of the world is the foundation, the voice of the people, that is the foundation of all the great composed music.

The composers that we remember are working within the laws of nature, within the laws of sound, in a way that their music seems to always have been there, to be crafted so that it is always there. So honor the folk music, honor the spirituals. Sing them. They’re good for your soul.

In this world now we are beset with electronic sounds. There’s nothing wrong with that exploration, but none of that sound is going to touch us in the way that I’ve just been describing. And we need that. We need to let down the boundaries that we put up around ourselves to shield ourselves from the bruises of everyday living and sink into a song that we can sing together . . . and meet each other on this common ground of what goes on in our inner lives. Try with any music that you are singing with your choirs and your students, your comrades, always to enter into the heart of the song so that you are allowing this communication to be total, to reach us where it really counts.

Our world needs this so much. We need to learn to listen to each other so carefully that we can respond in kind, [so] our voices can make the same sounds. [We need to learn] to listen to each other and to respect each other’s cultures so that we can easily pass from one to another, loving the sensation of letting ourselves open up to sound in a way that opens us up to be better human beings. To listen better, to respond better, and to feel that unity which is the hope of the world, for a peaceful future. Thank you.

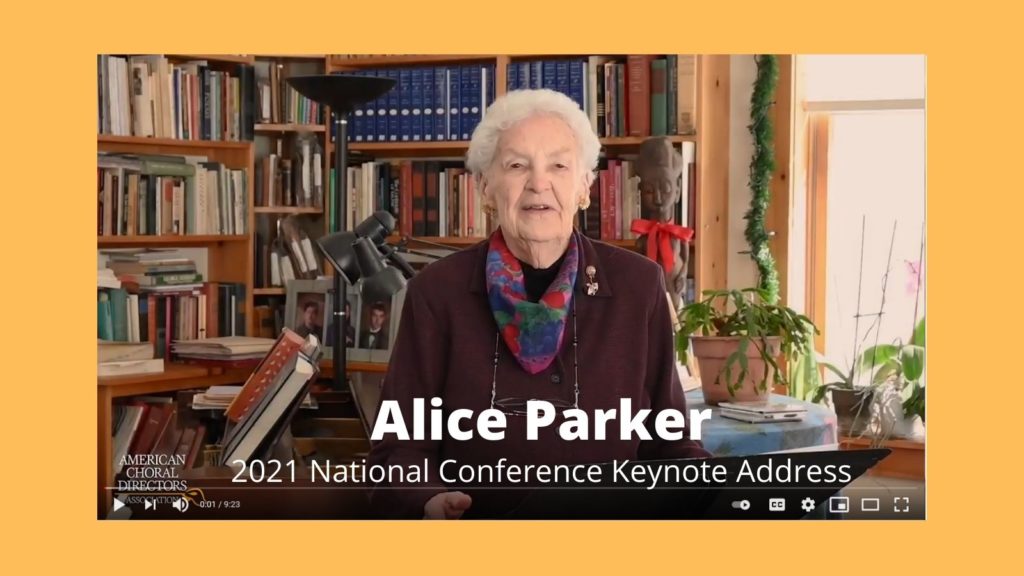

Alice Parker, internationally renowned composer, conductor, and teacher, studied composition and conducting at Smith College and the Juilliard School where she began her long association with Robert Shaw. The many Parker/Shaw settings of American folksongs, hymns, and spirituals from that period form an enduring repertoire for choruses all around the world. Her list of published compositions has over five hundred titles, ranging from operas through song cycles, cantatas and choral suites to many individual anthems. She has been commissioned by hundreds of community, school, and church choruses, and her works appear in the catalogs of a dozen publishing companies.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.