Recently, our district asked each content area to meet, discuss, and submit a plan for teaching our students how to study and prepare for local and state exams. My initial reaction was to roll my eyes and view this request as just another example of something that applies to other subjects and not to music education.

As I listened and watched my students study for their classes, I quickly realized that the district was correct. Unfortunately, many of the students do not have good studying skills. You can blame COVID, technology and social media, teacher-centered direct instruction, or silo education practices. But the main reason students struggle and lack sufficient studying or practicing skills is because we do not adequately teach, model, and reinforce these skills during instruction.

When was the last time your students heard you practicing your voice or instrument?

Show Your Work & Teach by Example

It basically comes down to labeling and explaining the teaching and learning techniques you use during rehearsals in real-time – to lead by example. You can start by writing a short outline of your lesson on the board or hold up and explain your lesson plan to the choir. In this way, your students will see and understand that each rehearsal has a focus, beginning, middle, and end. You can then share and explain to your students that they can use the same structure when planning their practice and study sessions.

Madeline Hunter has a great book you can turn to if you need a refresher on selecting lesson content and lesson planning. Take some time and check out Madeline Hunter’s Mastery Teaching: Increasing Instructional Effectiveness in Elementary and Secondary Schools. This book is a must-read for teaching any subject and a necessity for teaching music. It is a bit “old school,” but the pedagogical principles presented in this revised edition provide the essential structure that we must incorporate to successfully and effectively teach our students.

Chapter 10, Practice Doesn’t Make Perfect is a great place to start as you help your students learn how to structure and develop their own plan for practicing. To get the planning ball rolling, incorporate and label the following Four Principles to Improve Performance with your classes (Mastery Teaching, Hunter, p. 86).

Four Principles to Improve Performance

1. How much material should be covered?

Break down a section or skill into manageable sections

2. How long of a practice session?

Divide the practice session into 2 – 3 segments with a suggested total time of 30 – 45 minutes.

3. How often should I practice?

Use “Distributed Practice” Several short practice periods are more effective than one or two longer sessions

4. How well did the practice session go? Reflect and assess your progress by answering the following:

* What went well?

* What did not go well?

* How can you do better next time?

I use question number four all the time during instruction. It provides immediate feedback that helps the choir evaluate their work and discover areas where they need to grow and improve. By having the students learn to incorporate personal reflection in both the rehearsal setting and in their practice sessions, they begin to take more ownership of their learning and contribution to the ensemble.

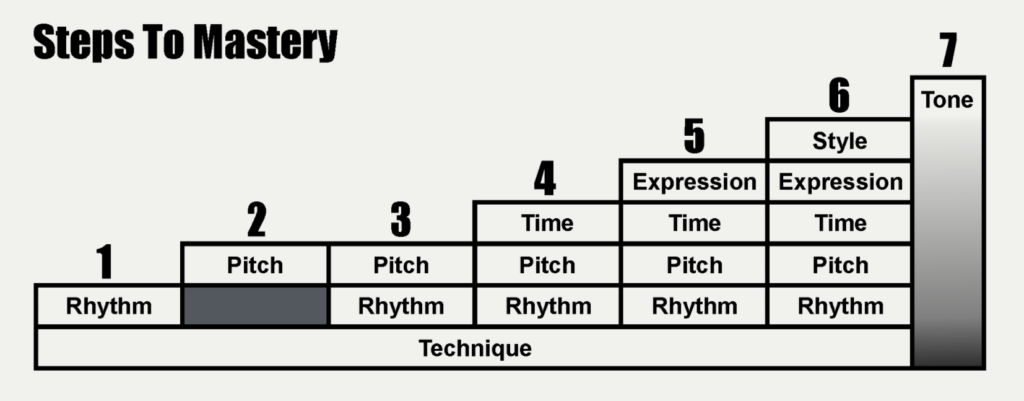

Steps to Mastery – shedthemusic.com

Another outstanding resource for high school and post-secondary teachers is the website The Shed (you will want to bookmark this resource!). In particular, our department decided to incorporate the Steps To Mastery into our instruction. The Steps To Mastery presents the organized steps that ascend in the order that our brains can “handle” as we learn new concepts and skills. We believe this paradigm will be a great reference and will use it as a guide to help students learn in class and practice at home.

Marcellus High School Three Tiers

For the past few years, the high school band director and I have collaborated and created a Three-Tier Learning system that we use during instruction. It fits well with the Sheds’ Steps to Mastery and provides us with a structure of skills and common terms that we use with our ensembles. For example, when an issue arises during rehearsals, we can easily select the Tier skill level – 1, 2, or 3 – and focus on one specific skill and outcome. Our students have become accustomed to this system and refer to it often during rehearsals, when working one-on-one, and when they work independently.

Tier 1 – Technical Skills – Knowledge and comprehension of basic musical skills such as

Pulse and Rhythm, Key Signatures and Solfege, and Posture and Tone Consistency

Tier 2 – Intellectual Skills – Application of Tier 1 skills and:

Application of Phrasing and Dynamics, Proper Intonation, Expression, and Articulation, etc.

Tier 3 – Emotional Skills – Interpretation and Synthesis of Tier 1 & 2 Skills

Musical and Stylistic Considerations, Repertoire Purpose & Function, and Time-Period/Style

From the Rehearsal Room to Independent Learning

Mitchell (2007, p 44) reminds us that each singer must develop their own method for learning new repertoire. For example, I use “RIP into Woodshedding” with my students during rehearsals and voice lessons as we work through new material or learn tricky spots. This sequence provides the students with a structure for learning while also allowing for individual autonomy and choice.

RIP into Woodshedding

Rhythm – Count or takadimi the selected music section and annotate if needed; perform rhythm on one pitch.

Intervals/Solfege – Write in the key and solfege; sing each pitch of the phrase devoid of pulse and rhythm (we call this technique “Stop-n-Lock”)

Practice – Count off, practice each chunk until correct, and then chain the successful chunks together.

The first step is to define and isolate only the rhythmic content – meter, time signature, and dominant pulse. When practicing, students are more successful when performing short 3 – 5 tonal pattern chunks and then chaining the successful patterns together. Next, define and isolate only the melodic content – tonality and key signature. Now comes the tricky part!

Combine the rhythmic and melodic content using a neutral syllable (Mitchell, 2007, p 47). * Do Not combine the rhythmic and melodic content until both are accurate (Ledbetter, 2016). And finally, add the text to the rhythmic and melodic content. If you want to have some fun, record this procedure in class and challenge your students to do the same by recording their practice sessions. Maybe for extra credit?

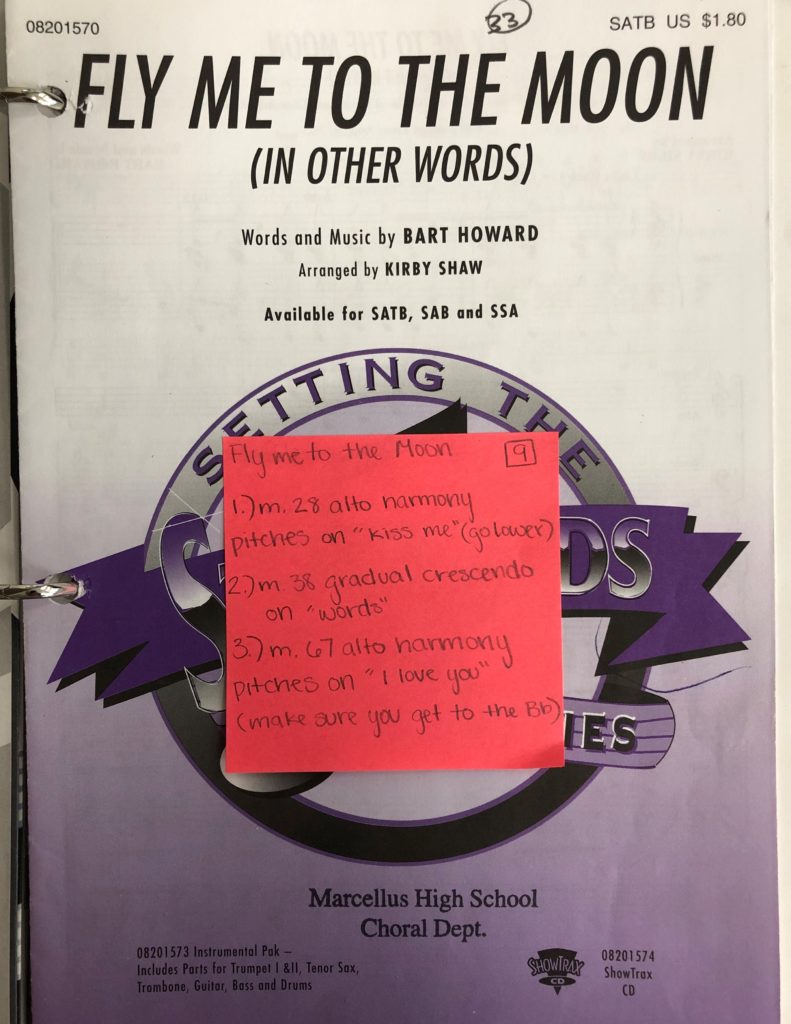

Readthrough Review

Sometimes, students say they do not know “where to start” when planning their practice session. So, I created the Readthrough Review activity to give them guided planning experiences during rehearsals. This process takes about seven minutes to complete and provides concrete examples of where the trouble spots are. If some students struggle or can not “find” the problems, I ask them to reach out and ask their neighbors for help.

Sight Reading Exercise Procedures (the total SR activity takes about five minutes)

1. Students identify and annotate the key signature

2. Teacher plays only the tonic triad or resting tone; students establish key center with so la so fa mi re ti do for major and mi fa mi re do ti so(si) la for minor.

3. Students sing their starting note (no pitch given)

4. Students count off singing their starting note – “one, two, ready go.”

5. Sing through the exercise – No Stopping!

The 10-Minute Window

Another way to help our students develop efficient practice and study skills during class and rehearsals is by teaching students to use the 10-Minute Window. When the ensemble encounters a challenging section of music, they are asked to:

(1) identify the area of concern,

(2) reflect on what they can accomplish in 10 minutes,

(3) collectively decide specifically what to “woodshed,” and

(4) set the timer for 10 minutes and go.

Through this process, students can select practice sections with efficiency in mind, learn more about their learning process, reflect on what they can accomplish in that time frame, and feel more reward and confidence from the thoughtful and deliberate preparation of their music.

TL;DR Teaching Music Practicing Studying Techniques

Why do most students find it difficult and challenging to practice and study independently? Because they have not been explicitly taught how to work independently and practice on their own. I know I was never taught how to practice and learn my music on my own. Like my students, I fell into the same trap many years ago: reading through my notes, memorizing the required information, and taking the test.

The problem is, that is precisely what many of our choir members try to do during our choir rehearsals. They come in and “re-read” the music, memorize their part, sing for the concert, and repeat the process. Unfortunately, not much learning going on.

But fortunately, if we provide a consistent presentation, awareness, reinforcement, and re-practice of the learning strategies and techniques we use during class, we can teach students autonomy and independent music-making.

The Agile Development Instructional Framework and Resources

The Agile Development Instructional Framework (ADIF) goal is to draw the students into an active teaching and learning environment where they learn to participate and think as autonomous musicians. This awareness is accomplished by presenting learning experiences that engage, challenge, and deepen our students’ cognitive and metacognitive processes, while also fostering independence and personal musical enjoyment. There is no longer a need for strict Banking Education or to retain the Silo Effect for each content area or skill. ADIF promotes and supports only one “Silo,” the Silo of metacognitive autonomy.

All activities, rehearsal strategies, and projects developed through applying the Agile Development Instructional Framework are research-based. They contain elements of the following teaching models and instructional theories: Self-Regulated Learning, Self-Directed-Learning, Experiential Learning Theory, Understanding by Design, Cognitive Coaching, and the Universal Design for Learning.

References

Gordon, E, E. (2021). Learning Sequences in Music: A Contemporary Music Learning Theory, Chicago, Il. GIA Publications, Inc.

Hicks, Charles E. “Sound before Sight Strategies for Teaching Music Reading.” Music Educators Journal 66, no. 8 (1980): 53–67. https://doi.org/10.2307/3395858.

Newport, C., (2007) How to Become a Straight-A Student. The Unconventional Strategies Real College Students Use to Score High While Studying Less. Broadway Books, NY

Mitchell, C. A. 2007, Audiation and the Study of Singing. FSU Digital Library

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.