“The great leaders are like the best conductors – they reach beyond the notes to reach the magic in the players.” Blaine Lee

A few weeks ago, I had lunch with an old friend, Jay*, who is a choir friend of mine. He teaches and directs in the city, so we don’t always have time to actually see each other. This time, everything worked out so we could get together. He caught me up with his family’s doings and I caught him up with mine. Then he told me why he really wanted to see me.

He asked if I remembered our choir director being especially perfect or if I ever did something some way because HE had done it that way. I told him no, while I admired our director and often think of him, I try to be myself as a conductor and director, not stuck in someone else’s image. My friend was relived, and then went on to explain why he wanted to talk about this particular subject.

Jay decided to join a select community chorus last year so he could regularly perform again. While he occasionally has a singing gig and certainly sings for examples as he directs his school choirs, he missed singing large choral works, directed by somebody else. He thought this group would be a perfect way to satisfy that urge. And while it HAS accomplished that, it has also shown him a dark side to community choral singing he never knew existed; the conductor cult.

I am sure some of you are confused with what I mean by a conductor cult. I do NOT mean the many students and assistants of nationally and internationally known, well-respected conductors of the past and of the present. I mean those conductors and directors who have set up their own little kingdom in their community, brain-washing singers to believe their way is the ONLY way.

Jay’s director, while a very nice guy, has created a cult of people who won’t listen to anyone else. When the director auditioned Jay, and realized he was a choral director too, asked Jay to run an occasional sectional—and told him he would be paid—and Jay agreed. Running those sectionals has been an eye-opening experience. Nothing he does, from his piano playing to his vocal technique suggestions, has been right. In fact, one of the singers he worked with asked the board not pay him since he was “doing everything wrong.” He was paid but Jay told the director he didn’t think it was a good idea for him to help with sectionals any longer. And when Jay spoke with the director, he didn’t seem surprised and was even a bit smug. It was almost as if the director set Jay up, with the intention of making sure Jay knew this was his territory, and not Jay’s.

Jay’s director is a decent musician but doesn’t know what all the fuss is about. There are cliques within the chorus, which are encouraged, that waste time and just perpetuate the cult. Jay doesn’t know if he’ll sing with them next year, he’s so disillusioned. But if he does, he knows he won’t help with sectionals.

In my conversation with Jay, I mentioned an experience I had with one of my church choir singers. We were warming up and I asked everyone to hum through a five-note scale. One soprano refused, and told me she was refusing. When I asked her why, she said her college choir director told them never to hum because it destroyed the voice. Huh? I explained I was using hums to get the voice warmed up, explained how to do a healthy hum but no, she would not do it. This lady was in her late 60s and her director must have been dead for at least a decade. She was devoted to his ways, and adamantly so. I told her to do what she wanted and moved on; you can’t argue with someone like that.

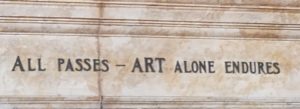

I think we do a disservice to our singers when we create a cult, an aura of infallibility around ourselves. There are plenty of ways—correct ways—to do things, not just one. We must be flexible and we must encourage our singers to be flexible. You never know, we might be even better if we open up our minds to something and someone different.

*Name Withheld

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.