continued from Solfège: Part 1: The Joy of Solfège

continued from Solfège: Part 1: The Joy of Solfège

Solfège: Part 2

The Legacy of Guido d’Arezzo

Solfège is a practical method for teaching sight-singing (singing music from written notation). Each note of the diatonic scale is assigned a solfège syllable. This practice is called solmization.

Solfège is the oldest and most widely used system for teaching sight-singing and the ability to read music in the world. It is a training technique and a tool, and it is common for students in music programs to use solfège every day as part of their musical training.

Guido d’Arezzo (literally, Guido of Arezzo, which is a town in Tuscany) was a Benedictine monk who lived during what is today called the Medieval Period. Guido is often referred to as the “Father of Music Education” and he is perhaps the most influential musician in history that you’ve never heard of. He was a musician, a teacher, and a music theorist, and he was widely known (among his musical contemporaries) during his own lifetime as the author of Micrologus, a treatise on teaching and singing Gregorian Chant and the composition of polyphonic music.

It was Guido who chose the solmization syllables that evolved into the system of solfège we use today.

The original syllables were:

ut re mi fa sol la si

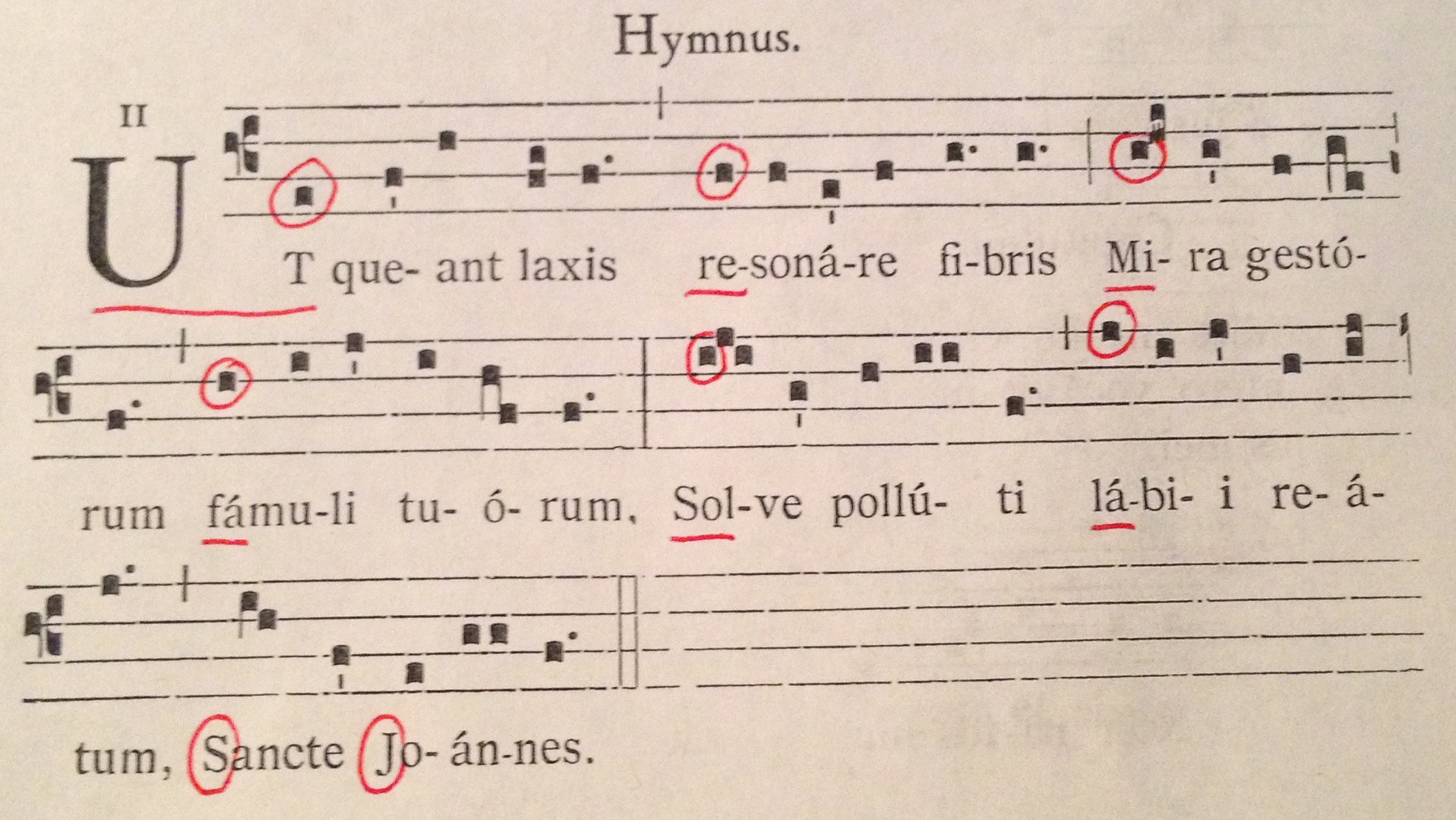

The first six syllables come from the first syllable in each line of the Latin hymn Ut queant laxis (Hymn to John the Baptist).

Ut queant laxis

Resonare fibris,

Mira gestorum

Famuli tuorum,

Solve polluti

Labii reatum,

Sancti Iohannes.

Each of the first six lines of this hymn begins on a note a step higher than the note the previous line began with.

For the seventh note of the diatonic scale, subsequent convention chose the syllable si, a contraction of the first two initials in Sancte Iohannes (Saint John). Originally Latin had no letter J.

Guido was responsible for other innovations in music and music education but today he is primarily remembered for the invention of solfège. Keeping to our discussion of that, we will leave him here.

Contemporary Solfège Systems

Although the system of solmization left to us by Guido d’Arezzo has been changed and developed over the last millennium to address the needs of musicians through great changes in musical style and complexity, the basic principles upon which it is based has not changed. Two of the original syllables – ut and si – have changed in some variations on the method to do and ti, and these are the syllables most familiar to those who use solfège in the United States.

do re mi fa sol la ti

As will be seen later, these changes have a distinct advantage for the system in that every diatonic syllable begins with a different consonant. This has several repercussions for the depth in which the system can be applied, and for the fact that when marking music with solfège syllables (for those in training), diatonic notes can be marked with a single letter (the first letter of the syllable) without confusion. (There are specific syllables for chromatic notes too; these will be addressed in Part 3.)

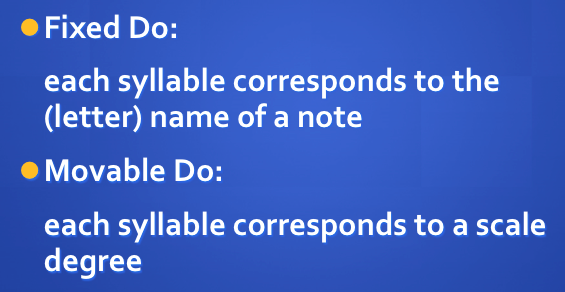

Basically there are three divisions in the way solfège is used throughout the world. The method is divided into two distinct styles: fixed do and movable do, and then movable do is further divided into two approaches.

In the fixed do system, every note is assigned a solfège syllable, and the assignment remains regardless of what key the music is in. For instance the syllable do is assigned to (letter named note) C, re is D, mi is E, etc. Therefore when singing a Major scale using the fixed do system, in the key of C Major the first syllable is do, but in the key of D Major the first syllable is re.

In the movable do system, the syllables correspond to scale degrees rather than fixed notes. So the tonic of a Major scale will always be do, regardless of what key the music is in. A C Major scale will always begin on do, as will a D Major scale – the tonic of a Major scale is always do in the movable do system.

Below is a generalization of the distribution of the use of these two systems throughout the world. This is a generalization, and exceptions exist probably in every country. Roughly speaking, those in countries that speak languages derived from Latin mostly use fixed do, whereas those that speak English or German tend to use movable do.

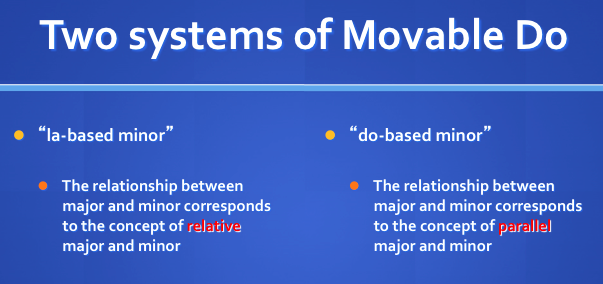

In addition, there are two systems of movable do.

In movable do with what is called “la-based minor”, in music set in minor keys the tonic is assigned the syllable la, whereas in the “do-based minor” system the tonic is assigned to do, just as it is in Major. La-based minor is set up to correspond to the relationship between relative Major and minor keys, and do-based minor corresponds to parallel Major and minor.

Which solfège system is best?

If you want to see musicians argue, just ask them why their system of solfeggio is the best.

~ Kurt Knecht

I’ve heard a lot of different opinions about this over the years. The most consistent thing I have noticed is that, regardless of which system it is, most musicians seem to prefer the one they know. People are loathe to change, and it becomes more and more true as they get older. I think it’s more important that teachers and students use solfège at all than which system they use. I believe that the use of the system itself improves musicians’ skill and understanding of the patterns and relationships inherent in music-making. I also believe that, with children especially, daily solfège practice done well and consistently will teach students to read music quickly and thoroughly, as well as provide an excellent tool for developing perfect intonation.

That said, I have noticed that most people regard fixed do as a more difficult system to master. Since the fixed do disciple must learn a different order and collection of pitches for every key, it is easy to see why. However, I also believe that the fixed do system is by far the best system to use if you are going to use it to work on learning post-common practice period literature. If you are a soprano preparing for your role of Marie in Wozzeck, fixed do will be your very good friend in helping you nail all those intervals.

If you are a school music teacher, however, or a choir director working with amateur musicians, movable do with la-based minor is more likely to be useful and approachable. School music teachers especially are often the only music teacher a student has, and as such are responsible for teaching the student everything about music – including not only vocal or instrumental technique, reading music notation, how to function in an ensemble, etc. but also whatever music theory they can squeeze in. A system that builds in awareness of the relationships between keys the way this method does is a great advantage, in an underhanded way. Teachers who use this system will see many “aha” moments from their students when after a year or two or three and all of those hours of solfège practice, everything lines up for a student and the patterns emerge, clear and resonating. The circle of fifths is not just an abstract chart or design, but a living breathing symbol of our entire tonal music heritage! Yes, movable do with la-based minor can do this for you and your students.

I’d like to make similar insightful observations about movable do with do-based minor, but unfortunately I have no experience with it. I can’t honestly think of any strong reasons to use it – I would encourage any adherents who read this to add them in the comments section below.

I have met other musicians, teachers, or directors who instead of solfège, use numbers. To them I would say: yes, by all means, use numbers too, it’s important for students to learn the scale degrees in as many ways as possible. But don’t use numbers as a substitute for solfège. As we will see in Part 3, solfège has a much deeper and more practical application than numbers. I also believe solfège is much more artistically satisfying and elegant, and it’s obvious that for singers at least, the fact that all of the vowels of the syllables are pure Latin vowels gives solfège a great advantage over numbers for working on tone and intonation.

As my primary use of solfège was as a K-12 music teacher, I always taught movable do with la-based minor to my students, and this is what we will consider more closely in Part 3.

©2015 Walter Bitner

Walter Bitner is a multi-instrumentalist, singer, conductor, and teacher, and serves as Director of Education & Community Engagement for the Richmond Symphony in Richmond, Virginia. His column Off The Podium is featured in Choral Director magazine, and he writes about music and education on his website Off The Podium at walterbitner.com.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.